My name is Joseph Davis, and I am a student in the Master of Science programme in experimental archaeology at University College Dublin. My bachelor’s degree was in Russian language and literature, but that was twenty-four years ago. Since then, I have worked in information technology.

Who am I?

How did I come to be involved with Seven in the Past?

I learned about the Seven in the Past project from a Facebook post, and became interested after watching videos from Alone in the Past. There was a need advertised on the website for foreign participants. Thinking that my experimental background combined with my admittedly rusty Russian might be useful, I contacted the team. After many emails and a meeting in Berlin, I decided to participate.

What do I hope to gain from the project?

I hope to increase my practical skills and experience with multiple aspects of medieval life in an immersive environment, and to gain a better understanding of how the various technologies and practices of the time may have worked together as a system in daily life, in the natural environment, and with the progress of the seasons.

What do I hope to bring to the project?

I hope to support the scientific value of the project through an experimental perspective. Specifically, I would like to identify opportunities for data collection and structured observation to assist in evaluating the hypotheses underlying the (re)constructions.

Experimental archaeology – what is it?

All evidence in the archaeological record must be interpreted to be understood, whether it is as seemingly simple as the use of a stone axe or as complex as the process of smelting iron. Archaeologists interpret finds based on previous research and often on ethnographic examples. Experimental archaeologists test these interpretations and relate our findings back to the archaeological record and to our overall idea of the past.

I will borrow a definition from Aidan O’Sullivan, the director for the centre for experimental archaeology and material culture at UCD.

Experimental archaeology is the (re)construction of prehistoric and medieval buildings, technologies, agricultural practices, and things; and their investigation through testing, recording and experience, so as to create a better understanding of people’s lives in the past.

What is meant by (re) construction?

(Re)construction, rather than reconstruction, calls attention to the fact that when we build a thing, for example, a house, that thing is a new thing based on our interpretation of the archaeological and historical record. A (re)construction represents a hypothesis about the past, a statement not that this is how the past was, but how it might have been.

Examples of two (re)constructions: early medieval Irish roundhouses.

I will show you two examples of (re)constructions of early medieval Irish post and wattle roundhouses. What we find when we find the remains of an early medieval roundhouse is usually only the post holes, and rarely, fragments of the lower walls. We do not know how the structures were built above the ground.

Most interpretations of these roundhouses are influenced by interpretations of Iron Age roundhouses at Butser Ancient Farm, which were in turn informed by African ethnographic examples. They are often built with a conical roof thatched in straw or reed, and the wattle walls are often daubed.

This example from the Ferrycarrig National Heritage Park in Ireland shows such a construction:

At UCD, Aidan O’Sullivan and Brendan O’Neill proposed a different interpretation of an early medieval post and wattle roundhouse.

The UCD roundhouse is based on a find at Deer Park Farms in Antrim, dated to the 8th century. It has no external or internal post holes, nor does it have evidence for daub (the “plaster” shown in the Ferrycarrig house). As the Deer Park Farms site was waterlogged, the wattle itself was preserved, and showed a complex and rope-like weave with the potential for great structural integrity.

Irish “beehive huts” show that a domed form was familiar.

O’Sullivan and O’Neill proposed a similarly-shaped woven structure, replicating the weave from Deer Park Farms:

Based on archaeobotanical and insect evidence from Deer Park Farms as well as historical examples from northern parts of Ireland, they chose heather for the thatching material rather than straw, resulting in a very different house for a similar plan:

Each (re)construction represents a different hypothesis based on similar evidence.

What is meant by an archaeological experiment?

A (re)construction on its own is not necessarily an experiment. An archaeological experiment has:

- Clear (and interesting) hypothesis or research question(s)

- Defined methodology

- Systematic data collection

- Analysis of results

Methodologies, data collection, and analysis may be highly technical and technological, or may be quite simple. What is important is that the methodology, data collection, and analysis are appropriate to answer the question being asked.

Example: Experimental investigation of early medieval souterrain ware

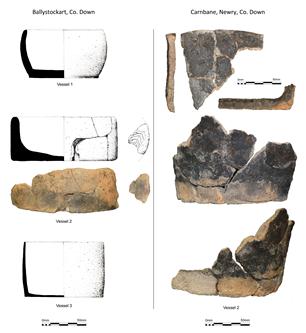

For example, consider the investigation of souterrain ware at UCD. This type of seemingly simple pottery appears in Ulster (the north of Ireland) in the early medieval period:

The Early Medieval Ceramics project considered several questions about souterrain ware, among them:

• How were they made?

• Were they as simple as we think?

• Were they necessarily made by specialist potters?

• What can we say of their use?

How were they made: what is the archaeological evidence?

The first step in investigating souterrain ware was to examine the archaeological evidence to determine from what it was made and how it was constructed. These pots appeared to have been coil built from boulder clay:

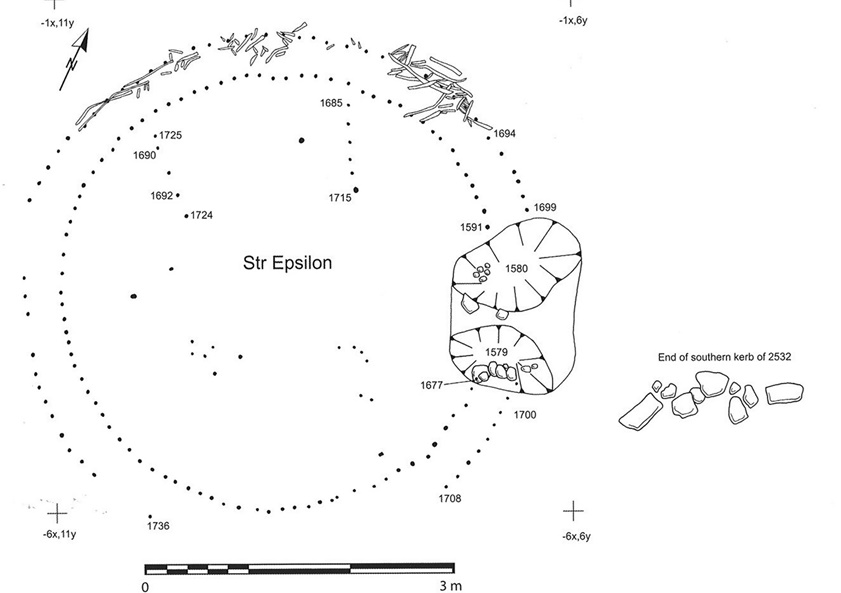

And fired in pits, or one by one in domestic hearths:

Given these starting points, what was the experiment?

Hypotheses:

• Souterrain ware pots did not need to be made by specialist potters

• Souterrain ware pots could be fired in pits and domestic hearths

Methodology:

• Have non-specialist potters attempt to create souterrain ware with boulder clay

• Fire pots in pits and domestic hearths

Data collection:

• Observe survival rates and final appearance of fired pots.

Analysis:

• Compare characteristics of pots to archaeological examples.

In this case, the reconstruction of the materials and method of manufacture of souterrain ware resulted in a product that was indistinguishable from the archaeological artifacts. Specialist potters were not needed to recreate souterrain ware, and souterrain ware could be fired in pits and domestic hearths.

With these (re)constructed pots, we can now test other hypotheses about souterrain ware and its use.

The potential experimental value of the Seven in the Past project

For the Seven in the Past project, participants will use an integrated suite of (re)constructed tools, technologies, and practices of ancient Russia in an immersive, daily, nine-month residency. Proposed past practices from growing, harvesting, and preparing food to maintaining structures and equipment will be implemented as part of everyday life.

This provides an opportunity for participants to test (re)constructions of ancient technologies and practices, and to perform multiple iterations of the same test. The long duration and 24/7 nature of the project would allow for the investigation of the impact of human activity on structures and other living and working areas that might be difficult at seasonally-occupied sites and sites only temporarily occupied. New questions and insights may also arise from the use of multiple technologies together that may not have arisen in isolation.

How might experimental archaeology be performed within the context of Seven in the Past?

Experiments may be integrated into daily activities, provided that:

- A research question exists concerning a technology, practice, or object to be used in the project

- A methodology has been defined based on previous research and best practice, of which participants have been informed

- Experimental replicas to be used have been created based on archaeological evidence and specific, defined hypotheses

- Data can be systematically collected and recorded

Conclusions

The Seven in the Past project provides an opportunity to experience the living conditions, technologies, and practices of the past as they may have been. By using (re)constructions based on archaeological evidence and past research, it may also serve as a platform for structured archaeological experiments, adding to the scientific knowledge of the lives of people in ancient Russia.