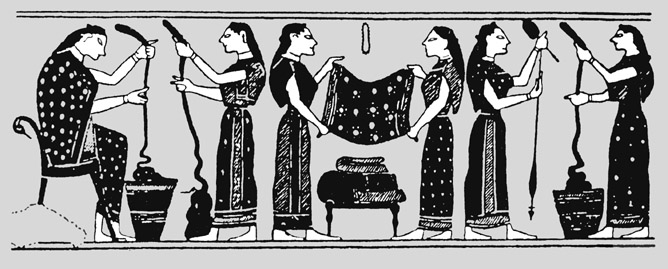

For Pavel’s clothes we used authentic materials. Shirts were made of homespun ethnographic linen. This is perhaps the most suitable available material, but it has a number of significant shortcomings. First, the ethnographic linen has a standard width of 35 cm, while the width of the early medieval linen was approximately 50–60 cm. Dress patterns strongly depend on width of linen. Due to lack of width, it’s necessary to change the authentic design. Third, density of linen. In early Middle Ages linen was much thinner. Nowadays there is very little thin ethnographic linen. Usually there is only coarse or very coarse fabric. Hereafter we want to start the process of creating linen from scratch. To plant flax, grow it, then collect, soak, scutch, break, knead, scratch, spin, weave and sew. Of course, this takes a lot of time and human resources (Fig. 1)

A similar situation is with dyeing. Some things, mainly garments, people dyed using natural dyes. As oxidizing agents and fixers of color we used modern alum (analogues of authentic alum). Some words about medieval dyeing. Ferruginous sands and ferruginous clay (there is a lot of it around Pavel’s farm) with madder roots give a gradient of colors from red to dark bordeaux. For black colour “oak / ink nuts”, knobs on oak leaves, were used (Figure 2). Urea by archeological data was used exclusively for dyeing with indigo, maybe with madder as well. For green color they used fermented oak and iron (oak bark ferments in a barrel). It was very difficult to fit a proper alum, so that the right colour would turn out.

Pavel had stocked up on those things that, in his opinion, were more prone to abrasion, but he had underestimated the degree of abrasion of others. He had only two pants. When the first pants were worn out, Pavel kept on darning them and wear. In general, darning and mending take a lot of time of the hermit, including precious daylight hours in winter.

So, Pavel had in the beginning of the project the following clothes:

— 5 pairs of shoes, one of them very old;

— 4 linen shirts;

— 1 woolen shirt;

— 2 pairs of woolen mittens;

— 2 pairs of woolen socks;

— 5 pairs of puttee;

— 2 linen pants, one is very ragged;

— 1 woolen hood and scarf;

— 1 sheepskin coat;

— 1 woolen coat.

All the shoes were made of leather of natural tanning and sewn by hand with waxed linen thread.

(Fig. 3) These are shoes based on the Haithaby model (type 6). There is a high boot top. These shoes fit for a cold time, so one of these was made 2 sizes larger. This allows to put a thick insole and extra fur or felt boot for better insulation from cold.

We’ve already said that no impregnation can keep shoes dry. At first, Pavel dried shoes on the stove. So, the leather lost its elasticity and started to wear out quickly, and wax from the threads melted and dried. So, the threads rot, and boots fell to pieces. Pavel had to repair these boots twice, although he had never do it before.

So, Pavel demonstrates medieval mentality, when one uses a thing, repairs it and not throws it away till it is completely unfit for use.

In the beginning of the project Pavel had a sheepskin coat, which was small for him. Pavel began to sew a bigger one. During the project Pavel impressively lost his weight, so the former coat became a right size and the latter became too big. (Fig. 4)

By the middle of the project Pavel made a new fur-cap of sheepskin: it is very correct from archaeological point of view. Although Pavel decided not to make a linen or wool covering, which would protect the skin from moisture and prolong the lifespan of the cap.

Pavel’s socks and mittens were knitted with one bone needle. It’s one of the most archaic ways of knitting, which is now preserved in some parts of Karelia. The prototype of the mittens is from medieval York. They were knitted from self-spun wool and dyed with buckthorn. (Fig. 5)

Pavel’s cloak was rectangular, sewn from undyed pieces of grey wool. Pavel fastens it on his throat with a fibula. The cloak is warm and light. (Fig. 6).

So all of Pavel’s clothes have its history in the project. Some have been perished under the harsh conditions, some keep on serving to Pavel.